Announcing the 2025 Fulbright New Zealand Cohort

Fulbright New Zealand is delighted to announce the recipients of the 2025 New Zealand Graduate and Scholar Awards.The grantees in each category are as follows. Fulbright NZ Scholar Awards Fulbright Scholar Awards are for New Zealand academics, artists or professionals to lecture and/or conduct research at US institutions. The following

Bright Sparks Summer 2025

The latest edition of Bright Sparks has arrived! Brimming with news, features, photos and more, it’s the best way to keep up to date with all things Fulbright NZ. In this issue: All that and much more! Click here for the digital copy, or get in touch if you would

Announcing the 2025 Fulbright US Cohort

Fulbright New Zealand is thrilled to announce the 2025 cohort of US Scholars, Graduates, and Specialists. Fulbright New Zealand Executive Director, Penelope Borland, says the latest group of US grantees travelling to Aotearoa is testament to a deeply held, shared commitment to the betterment of our world. “Year after year

Announcing the 2025 Ian Axford Fellows in Public Policy

Fulbright New Zealand is pleased to announce the recipients of the 2025 Ian Axford Fellowships in Public Policy. These fellowships are for outstanding mid-career US professionals to research and gain first-hand experience of public policy at a New Zealand government organisation. Ian Axford Board Chair Roy Ferguson says the quality

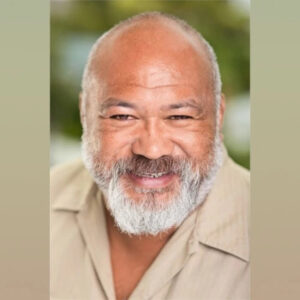

David Fane awarded 2024 Fulbright-Creative New Zealand Pacific Writer’s Residency

Fulbright New Zealand and Creative New Zealand are pleased to announce that David Fane is the recipient of the 2024 Pacific Writer’s Residency. This award is for an established New Zealand writer of Pacific heritage to carry out work on a creative writing project exploring Pacific identity, culture or history at

Fulbright-Ngā Pae o te Māramatanga 2024 Graduate Award Announcement

Finley Ngarangi Johnson to travel to Hawai’i, Duluth, and Baltimore as a Visiting Student Researcher Fulbright New Zealand and Ngā Pae o te Māramatanga, New Zealand’s Māori Centre of Research Excellence, are pleased to announce that Finley Ngarangi Johnson (Rongomaiwahine, Ngāti Kahungunu) is the 2024 recipient of the Fulbright-Ngā Pae

Stage direction and hate speech detection feature in diverse cohort of 2024 Fulbright NZ Graduates

2024 Fulbright New Zealand Graduate Awards announced Fulbright New Zealand has today announced the 15 recipients of this year’s New Zealand Graduate Awards. These prestigious awards enable New Zealand graduate students to undertake postgraduate study or research at US institutions. Subjects covered by this year’s cohort form a particularly diverse

Fulbright Outreach 2024

What would you do with a Fulbright? Have you always wanted to study or carry out research overseas? A Fulbright Award could take you to a leading institution in the United States. We have a range of awards for graduates, scholars, creatives, professionals and more. Want to know more? Stand

Fulbright-Ngā Pae o te Māramatanga 2024 Scholar Award Announcement

Dr Hona Black to explore language interference at the University of Hawai’i Fulbright New Zealand and Ngā Pae o te Māramatanga, New Zealand’s Māori Centre of Research Excellence, are delighted to announce that Dr Hona Black (Tūhoe, Te Whānau-a-Apanui, Te Whakatōhea, Tūwharetoa) is the 2024 recipient of the Fulbright-Ngā Pae

Language, Nutrition and Criminal Justice feature in 2024 Fulbright NZ Scholar Awards

2024 NZ Scholar awards announced Fulbright New Zealand has announced the seven recipients of the 2024 NZ Scholar Awards. These prestigious awards are worth up to US$37,500 for New Zealand academics, artists and professionals to study and/or lecture at a US institution of their choosing. Research subjects covered by this

Announcing the 2024 Fulbright US Scholars and Graduates, and Ian Axford Fellows

Wide range of talents in the 2024 cohort of US Scholar and Graduate Award winners Fulbright New Zealand is proud to welcome the 2024 cohort of US Scholar and Graduate Award winners. Fulbright NZ Executive Director Penelope Borland says the calibre and quality of the 2024 grantees is as impressive

Announcing the 2023 Fulbright NZ cohort

Award recipients to be honoured at the 2023 Fulbright New Zealand Awards Ceremony WELLINGTON, NEW ZEALAND, Tuesday 13 June 2023 — Fulbright New Zealand is delighted to announce the 2023 Fulbright New Zealand scholarship award winners. The new cohort will be honoured at the 2023 Fulbright New Zealand Awards Ceremony